"They Don't Call for Their Parents, They Say 'Long Live the Great Leader'": Lt. Gen. (Ret.) In-Bum Chun on North Korea's Cyber Superpower Status, Why Cognitive Warfare Is the Real Threat, and the Russian Tech Transfer That Should Terrify Us

In a quiet corner of Seoul, where the Han River meets the city's gleaming financial towers, Lieutenant General (Retired) In-Bum Chun builds plastic models in his study. The same hands that once commanded South Korea's Special Forces—that signed orders for missions along the world's most militarized border—now carefully assemble miniature aircraft and tanks. It's a hobby that requires patience, precision, and an eye for detail. The same qualities, he tells me, that allowed him to survive 38 years in an army where he "tried very hard to get thrown out" but instead kept getting promoted until he wore three stars.

At 67, Chun represents a vanishing breed: a Korean military officer who speaks English with native fluency, who understands both American swagger and Korean restraint, who can translate between two cultures that desperately need each other but often talk past one another.

When he describes North Korean soldiers in Ukraine blowing themselves up rather than surrender—their final words not pleas for family but "Long live the great leader"—his voice carries the weight of someone who has stared across the DMZ for decades, studying an enemy that the West consistently underestimates.

Given your experience as Commander of Special Warfare Command and your current role at the National Institute for Deterrence Studies, how has North Korea's asymmetric warfare capabilities evolved, particularly in space and cyber domains that could threaten critical infrastructure?

Before diving into North Korea's capabilities, Chun offers context about his unique position to assess them. "I served in the Korean military and retired in 2016 as a three-star general. I was an infantryman who commanded combat units up through Infantry Division, and finally, I was given the honor of commanding the Korean Special Forces."

His linguistic abilities set him apart in the Korean military hierarchy. "What's unique about my career is that I speak English the way I do now. In my country, especially in my generation—I'm 67 years old—there are very few people who speak fluent English, and probably none who speak English like I do in the military."

This fluency came from an unusual childhood. "I was fortunate to come to the United States at age seven in 1965, where I lived for three and a half years. My mother had the foresight to ensure that I didn't forget English." The timing was significant—1965 marked the height of U.S. military involvement in Vietnam and a period of strengthening U.S.-ROK military cooperation, with South Korean forces deploying to Vietnam alongside American troops.

His military journey wasn't straightforward. "Ever since I was a little boy, I wanted to be a soldier, though I made the mistake of becoming an officer. I wanted to quit when I was a lieutenant colonel—I tried very hard to get myself thrown out, but I was unsuccessful and rose to three-star. Here I am."

Even in retirement, he remains engaged with security issues. "Since retiring, I've focused on maintaining and strengthening the ROK-US Alliance and improving the capabilities of the Korean military. I also serve the community in other ways—I'm on the board of directors for the Korea Animal Welfare Association, where I've served for the past 10 years. And I'm a modeler—not in bikinis, but I make plastic models."

With that background established, Chun turns to North Korea's evolving threat. "The term 'asymmetric capabilities' is used very widely in Korea, but in this case, it specifically focuses on cyber and space. The North Koreans have been very creative because they've been struggling to survive as a regime."

North Korea: The Unexpected Cyber Superpower

Key Cyber Warfare Assets

Major Cyber Operations Timeline

He explains their cyber strategy with stark clarity. "They realized that in the cyber realm, they had an opportunity to create an army of cyber warriors with very low financial investment. If you're a teenager with mathematical skills, the North Korean government has the ability to recruit you. After training, they turn you into either a hacker or a programmer who develops attack programs."

The results speak for themselves. "North Korea is considered a cyber superpower in the security realm. They rank alongside the United States, Russia, China, and Israel." What gives them this edge? "North Koreans have the advantage of being able to pull in their best mathematical minds, but they also don't have to follow any international norms or laws. They don't care if they get caught."

The evidence is extensive. Bureau 121, North Korea's elite cyber warfare unit established in 1998, consists of approximately 6,000 hackers who have conducted operations worldwide. The Lazarus Group, linked to the 2014 Sony Pictures hack and the 2017 WannaCry ransomware attack, has stolen an estimated $2 billion in cryptocurrency to fund North Korea's weapons programs.

"We've seen through activities like Bureau 121 and the Lazarus Group that they've been very successful. They've attacked the Korean power grid, our media systems, and there's speculation they've infiltrated our election infrastructure. All of that is quite disturbing to us."

The attacks Chun references have been devastating. In 2013, North Korean hackers paralyzed South Korean banks and broadcasters, affecting 32,000 computers at media companies and financial institutions. The 2014 Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power hack saw hackers steal internal documents and threaten to destroy nuclear reactors unless they were shut down.

On space capabilities, North Korea lags but aspires. "Space-wise, North Korea has been lacking in sophisticated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance satellite capabilities, but they maintain very strong aspirations to improve. They've been launching rudimentary satellites—most have failed, but some have succeeded. They've expressed strong ambitions to develop military reconnaissance satellites."

North Korea's space program dates back to 1998 with the failed Kwangmyŏngsŏng-1 launch. They achieved their first successful orbital insertion in 2012 with Kwangmyŏngsŏng-3 Unit 2, though the satellite reportedly tumbled and never functioned properly. More recently, in November 2023, North Korea successfully launched its Malligyong-1 reconnaissance satellite, claiming it transmitted images of U.S. military bases in Guam and Hawaii.

The potential for escalation is real. "The possibility of North Korea developing counter-space assets is right there—missile-based anti-satellite tactics, even an EMP burst at altitude is something that is theoretically possible. All of this is a threat in that realm." But Chun saves his most ominous observation for last. "Right now in Russia-Ukraine, the North Koreans are thought to provide 40% of the ammunition used by the Russians, and they must be getting a lot in return. It's not just rubles."

The New Axis: North Korea-Russia Military Partnership

Scale of Cooperation

Technology Transfer Concerns

Strategic Implications

| Domain | Risk Level | Key Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Technology | Critical | Potential transfer of weapons-grade materials |

| Space Capabilities | High | GLONASS access, anti-satellite weapons |

| Electronic Warfare | High | Krasukha-4 system (300km jamming range) |

| Drone Technology | Urgent | Battlefield-proven tactics from Ukraine |

You oversaw Iraqi elections in 2004 and have extensive experience in alliance management. How do space-based assets factor into modern electoral security, and what vulnerabilities do you see in democratic processes that adversaries could exploit through space-based attacks?

"I was in charge of the first free and fair elections in Iraq in 58 years, in 2004," Chun begins. The Iraqi parliamentary election of January 2005 (which Chun helped secure in 2004) saw 8.5 million Iraqis vote despite insurgent threats, marking a pivotal moment in post-Saddam Iraq. "Unfortunately for us, our main threat was suicide bombings and IEDs to disrupt the elections. But in my society right now, Korea—as you know—is one of the most wired countries in the world. We rely on everything."

South Korea indeed ranks among the world's most connected nations, with 96% internet penetration and the fastest average internet speeds globally. This connectivity extends to its democratic processes, with electronic voting systems and real-time vote counting that depend heavily on satellite communications and GPS timing.

He explains how dramatically the threat landscape has evolved. "If I'm on a speeding bullet train and I can't stream, I'll sue the rail company. We are so dependent on connectivity now. For elections, space infrastructure is critical for data transmission, time synchronization, surveillance, and early warning about physical disruption."

The vulnerabilities are extensive. "Because Korea is so wired, GPS disruption, GPS spoofing, satellite jamming, and cyber attacks on the ground segment of the link are always persistent threats. North Korea knows how to use their limited resources very effectively, so they have been very focused on developing GPS jamming and satellite jamming capabilities, which is not that hard."

He provides a concrete example. "For about 20 years, in the northern sections of Seoul, we have seen the North Koreans deliberately disrupting our GPS, which is quite dangerous, especially for flying aircraft. So we know that they will do that, and they have the capability to do that. Although military GPS is a little bit better protected, this is still a challenge."

These GPS attacks have been well-documented. In April 2016, North Korea jammed GPS signals affecting 1,007 aircraft and 715 ships. The attacks originated from multiple sites near the border, including Kaesong, Haeju, and Mount Kumgang. South Korean officials reported that the jamming signals reached up to 100 kilometers into South Korean territory.

The alliance response has been crucial. "Korea and the alliance between the United States really focus on maintaining vigilance and countermeasures." Electoral integrity faces particular risks. "So there's a good segment in Korean society that is very, very concerned. We're very concerned because of the potential influence that other countries can have towards South Korean internal politics. And I'm not afraid to name China."

The ROK-US Alliance: 70 Years of Transformation

South Korea's Economic Miracle

Alliance Impact

From Aid Recipient to Global Contributor

China's influence operations in South Korea have been well-documented, from economic coercion during the THAAD deployment to social media manipulation campaigns. The 2017 THAAD dispute saw China impose unofficial economic sanctions that cost South Korea an estimated $7.5 billion.

With your deep knowledge of the ROK-US alliance structure, which space-dependent military capabilities are most vulnerable to Chinese or North Korean interference? Walk us through the cascade effects of GPS or satellite communications that were compromised during a crisis on the Korean Peninsula.

"You asked about the alliance between the United States and Korea," Chun begins, offering crucial context. "The Republic of Korea is 77 years old, and this alliance is over 70 years old. The Republic of Korea is probably the single most successful example of how American assistance can lead to success."

The ROK-US Mutual Defense Treaty, signed on October 1, 1953, just months after the Korean War armistice, has evolved from a simple security guarantee to one of America's most comprehensive alliance relationships. Today, 28,500 U.S. troops remain stationed in South Korea, operating from major installations like Camp Humphreys, Osan Air Base, and Camp Carroll.

He reflects on the transformation. "When the United States became a global leader, the Marshall Plan helped rebuild already established societies in Europe. Korea was different. We had nothing. We were like a country in Africa somewhere—poor, war-torn, barely functioning. But 70 years later, thanks to American support, we’ve become a vibrant democracy and a global economic player contributing not only to Northeast Asian security, but to the world at large."

The numbers support his assessment. South Korea's GDP has grown from $2.7 billion in 1960 to over $1.8 trillion today, making it the world's 12th largest economy. From receiving aid, South Korea became a donor nation, joining the OECD Development Assistance Committee in 2010. The gratitude runs deep. "Seven or eight out of ten Koreans believe we owe this transformation to the United States. Personally, I think this kind of over-reliance can be risky—old habits die hard—but that’s where we are."

He emphasizes the mutual benefits. "The United States has also benefited from this relationship. American prestige and influence in Northeast Asia—where roughly 30% of the world’s wealth is generated—have been reinforced by the alliance. That’s a solid return. Overall, we’ve built a very strong partnership." Still, there are modern tensions. "Things have gotten a little hectic—your president has thrown wild-card tariffs at us. But we’ll get through it. That said, 70 to 80 percent of Koreans still understand how vital our relationship with the United States truly is."

Returning to space vulnerabilities, Chun explains Korea's efforts. "Space—and the infrastructure it enables—is absolutely essential for a modern nation to remain free, to communicate, to make informed decisions, and to secure its interests. That critical infrastructure depends on space." He continues: "We Koreans are now building and launching our own communication satellites. We’ve partnered with U.S. rockets and, before the war, Russian ones. Surveillance capabilities are improving with new launches, but it’s still not enough. We’re making progress, but we’re not fully there."

South Korea's space program has accelerated dramatically. The country launched its first domestically-built rocket, Nuri, in 2022, and plans to launch 130 satellites by 2030 under its satellite development roadmap. In December 2023, South Korea successfully launched its first military reconnaissance satellite aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

The alliance remains critical."No country ever has enough capability on its own—and we understand that. That’s why the alliance remains essential."

As someone who has worked extensively with Combined Forces Command, what keeps you up at night about space domain awareness and protection in the Indo-Pacific? Are we adequately preparing for multi-domain operations that include space as a warfighting domain?

"What keeps me up at night?" Chun pauses thoughtfully. "What really concerns me is that, for a variety of reasons—political, or just ignorance—we continue to underestimate North Korea. For the past 30 years, experts have insisted the regime would collapse on its own. Well, it hasn't happened."

Indeed, predictions about North Korea’s demise have repeatedly fallen short. When Kim Il-sung died in 1994, many analysts expected the regime to fall. The famine of the 1990s, which killed between 600,000 and 1 million people, was believed to be a likely trigger for revolution. When Kim Jong-il died in 2011, skeptics doubted that his young and untested son, Kim Jong-un, could maintain control. Every time, those assumptions proved wrong.

Chun points to the regime’s continuity. "Kim Jong-un, who is now in power, started out as a very young man. He’s still in his 40s—and if you go by genetics alone, with his father and grandfather both living into their 70s, he could be around for another 30 years. He can play the long game."

He’s troubled by strategic miscalculations. "And he’s not stupid, either. What’s really frightening is that he’s lucky. I mean, who would have predicted the Russians would struggle like this in Ukraine? And now Putin is turning to Kim Jong-un for support. Because of all these factors, he’s in a strong position. But my real concern is that we’re underestimating both his capabilities and his sheer luck."

Chun then pivots to China and Taiwan. "Right now in South Korea, there’s more interest than usual in what’s happening with Xi Jinping. Something seems to be shifting in the Chinese leadership. There are rumors that his anti-corruption campaign, particularly targeting the military, may have backfired. Some say his loyalists have already been sidelined—putting it mildly. Others claim he’s physically ill, that he may have suffered a stroke."

Xi Jinping’s sweeping anti-corruption drive, launched in 2012, has led to investigations of over 4.7 million officials—including more than 200 generals and admirals. Recently, purges within the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force, which oversees China’s nuclear arsenal, have raised eyebrows both domestically and abroad.

"But despite his two-month absence from public view, Xi has reemerged. One theory is that the Chinese system will ease him out quietly, without surface-level violence. Another theory is that’s not how power works—no one in China could sleep soundly while the 'great panda bear' is still breathing. So blood must be shed. Whatever the outcome, a drastic shift on the Chinese mainland would be bad for everyone."

He offers intelligence cues to monitor. "Hopefully, this transition—if it’s coming—can happen without chaos or violence. One thing to watch: in early August, there’s a major People’s Meeting in China. Where Xi Jinping sits, who looks at him, who he looks at—all of those subtle signals will be indicators. We have a couple of weeks to wait and see how it plays out."

On Taiwan, Chun offers a blunt take. "Taiwan is important. But in my view, Taiwan is already independent. So while the Chinese leadership insists otherwise, the reality is that Taiwan functions as a sovereign nation. For China to invade Taiwan—and for the United States to go to war with China over it—that’s an extremely serious concern."

He acknowledges the nuclear dimension. "If it comes to that, we’ll have to find some sort of middle ground. If not, it could escalate to nuclear war. That’s hard to even imagine. I mean, surely not everyone is that crazy—so for now, I’m not going to worry about it."

Chun understands why some South Koreans feel conflicted. “A lot of Koreans are worried that we could get dragged into a conflict we want no part of. But that’s naive. Those kinds of sentiments are being amplified by politicians who believe we can somehow remain neutral in a war between the United States and China. That’s just wishful thinking. Not only do we have a mutual‑defense treaty, but China is right next to us.”

He outlines South Korea’s likely role in a broader regional conflict: “If a conflict breaks out, our initial contribution would likely be in escort missions and logistical support. But during those operations—if our ships or aircraft are attacked—then we’re involved. We can’t avoid getting involved, period. And another concern is that North Korea might see that as an opportunity to act."

His personal commitment is crystal clear. "Aside from the fact that we’ll be affected by any greater war involving the United States and China, Koreans need to accept that the U.S. is our ally—and we have alliance obligations to uphold. No matter what my government decides to do, I’ll be in a BDU—either hauling supplies for you guys, or I’ll be ready to fight."

If you were advising allied nations on $100 million in space security investments today, where would you focus those resources to best deter aggression and protect critical space infrastructure? Which technologies offer the highest return on deterrence investment?

"If I had a sizable budget," Chun begins, "I’d allocate half of it toward expanding low Earth orbit capabilities—either through direct Korean assets or by leveraging commercial systems we can access. I'd focus on hardening the satellites we already have, making them more maneuverable. We also need regional satellite communications redundancy. That means either building more comms satellites or ensuring we can link into others when needed."

$100M Space Security Investment Roadmap

Primary Investment Allocation

- Hardened, maneuverable satellites

- Regional communications redundancy

- Commercial LEO partnerships

- Threat identification algorithms

- Automated response systems

- Pattern recognition capabilities

- Training & education programs

- Commercial system expertise

- Multi-domain operations skills

- Multi-altitude detection

- Small object tracking

- Network integration

Additional $100M Priority: Directed Energy Weapons

Iron Beam Advantages

The focus on low Earth orbit (LEO) reflects current trends. Companies like SpaceX, OneWeb, and Amazon's Project Kuiper are deploying thousands of satellites in LEO, offering more resilient communications than traditional geostationary satellites. LEO satellites orbit at 500-2,000 kilometers altitude, compared to 36,000 kilometers for geostationary orbit, providing lower latency and requiring less power to reach.

Chun sees artificial intelligence as another critical investment area. "AI could really help with early detection. That’s where I’d put serious attention. But as you said, we also need to be more proactive. We need maneuverable satellites on orbit that can respond quickly. And we need redundant GPS-like capabilities so we’re not reliant on just one system." The U.S. Space Force has already begun implementing similar concepts through its Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, planning to deploy hundreds of satellites in LEO to provide resilient missile tracking and data transport capabilities.

Chun believes commercial space assets hold massive untapped value—if nations know how to use them. "I’d spend a lot of that budget on commercial satellites that already exist. These systems can offer immense capabilities, but if you don’t understand how to use them, it’s all wasted." He illustrates with a relatable analogy. "It’s like giving someone a Samsung S24—which is what I have—and they don’t use even half of what it can do, simply because they don’t know how. It’s not just about owning the best tech; you need the knowledge to use it effectively."

That’s why he believes human capital must be part of the equation. "I’d invest heavily in training and educating people. There’s significant commercial capability out there, but it only becomes valuable in the hands of capable, well-educated users."

When asked about the most urgent countermeasure, Chun doesn’t hesitate. "Lasers. Lasers. Give me another $100 million, and I’d put every cent into lasers." He points to current breakthroughs. "The Israelis have something called Iron Beam." Developed by Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, Israel’s Iron Beam is a directed-energy weapon designed to intercept rockets, mortars, and UAVs at a remarkably low cost—about $3.50 per shot, compared to $50,000 to $100,000 for traditional interceptor missiles.

"It’s not fully operational yet," Chun notes, "but they’ve had to use it in real situations. They identified issues, and they’re fixing them. Laser systems are the only viable countermeasure to these $200 drones—you can’t shoot them down with $200,000 missiles. That’s just not sustainable."

Detection infrastructure is equally vital. "We need radars. One radar won’t cut it. Instead of focusing separately on high-altitude, mid-altitude, low-altitude, and terminal-stage detection, we need integrated radar systems that can track threats—especially small ones—at multiple intervals. Then we can pair those with lasers, which are far more affordable, to neutralize them."

But the most daunting challenge? Hypersonics. "And then, of course, there are hypersonic weapons. Whether people want to admit it or not, that’s a very real and very big challenge right now.” Hypersonic weapons, which travel at speeds exceeding Mach 5 (over 3,800 mph), pose unprecedented challenges to existing defense systems. Russia's Kinzhal missile and China's DF-ZF hypersonic glide vehicle can maneuver unpredictably at extreme speeds, making interception extremely difficult.

"The thought of those things is terrifying," Chun admits. "As a military man, the logical answer would be to shoot first. But then you’re left with all the uncertainties—how do you know it’s the right decision? So I’ll leave that to the younger generation. I’m just glad I’m an old guy. I can talk about these things."

Given recent developments with North Korea's military cooperation with Russia, including potential technology transfers and joint military exercises, how do you assess the implications for space-based threats to allied nations? What new capabilities might emerge from this partnership that could target critical infrastructure in South Korea, Japan, or the broader Indo-Pacific region?

"About two years ago, when the first signs of North Korean–Russian cooperation began to surface, it started with reports that North Korea was sending ammunition to the Russian front," Chun recalls. Initial U.S. intelligence in late 2022 indicated that Pyongyang was supplying Soviet-era artillery shells to Russia, with estimates in the thousands of rounds.

"And of course, the experts at the time said, ‘Well, 50% of that ammunition is probably duds.’ There was this belief that it wouldn’t amount to much. Most experts insisted the relationship would be short-lived and that whatever Russia gave North Korea would be minimal."

Chun wasn’t convinced. "I asked them, ‘Why do you think this time is the same as the past 50 years?’ And their response was basically, ‘Because it always has been.’ But I said no. This time is different. The Russians are desperate."

Time has proven him right. "Now we’re seeing thousands of North Koreans deployed to the Russian front, with reports suggesting another 30,000 could be rotated in," he says. As of October 2024, U.S. and Ukrainian intelligence confirmed that approximately 10,000 North Korean troops had been deployed to Russia’s Kursk region.

What’s more surprising is the reception. "The Russians have great admiration for these North Koreans. Even the Ukrainians are saying, ‘We don’t understand why they fight so hard. They’re disciplined, effective, and evolving rapidly as infantrymen.’"

But the compensation for North Korea extends well beyond arms or cash. "This isn’t just about money, fuel, or food. What really worries me is the potential for significant technological transfer—whether officially sanctioned by Putin or not. Even if he says, ‘Don’t give them that,’ how hard would it be for a North Korean official to bribe a Russian scientist? Not hard at all."

Historical precedent underscores his concern. "In the mid-1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, there were Soviet states selling weapons-grade uranium. It’s happened before." The International Atomic Energy Agency has documented over 3,000 cases of unauthorized possession or trafficking of nuclear materials since 1993.

Chun is direct in his conclusion: "This relationship will continue as long as Putin is alive." And it’s not just military integration. "There are reports that Russia is preparing to issue 200,000 student visas to North Koreans. But these aren’t students. They’re workers—laborers being sent to help rebuild the occupied territories in Ukraine. The scale of this cooperation is expanding fast."

He turns to space technology. "Let’s talk about the real threat—our favorite subject: satellites. I’m certain the Russians are transferring satellite and rocket technologies to North Korea. GPS disruption. Spoofing technology. The whole bucket list of things North Korea has been dreaming of."

Russia's expertise in these areas is extensive. Their GLONASS satellite navigation system provides global coverage, and they've demonstrated sophisticated electronic warfare capabilities in Syria and Ukraine, including the Krasukha-4 system that can jam satellite communications and radar systems at ranges up to 300 kilometers.

But the threat doesn't stop with Russia. "This isn't just our problem. There are strong suspicions of deep ties between North Korea and Iran. If you look at Iranian rockets, they look almost identical to North Korean designs." The Shahab-3 missile, for instance, is widely believed to be based on North Korea’s Nodong-1. "And while people praise Iran’s drone capabilities, I suspect North Korea had a hand in developing them. Back in the mid-to-late 1990s, during the annual parades, North Korea used to show off large drones. Then, suddenly, they disappeared. It makes me wonder if they weren’t part of something bigger."

He stresses the importance of what’s unseen. "We spend so much time analyzing what North Korea shows us. But we should be paying even more attention to what they don’t show." His greatest fear stems from battlefield evolution. "What really keeps me up at night about the Russia–Ukraine war is this: the North Koreans are learning, firsthand, the power of drones. They've seen how drones have changed modern warfare, and now they get it."

The Ukraine conflict has indeed become a proving ground for drone warfare—from modified DJI quadcopters dropping grenades to Iranian-made Shahed-136 loitering munitions. These systems have reshaped battlefield dynamics. "And now North Korea understands. The terrifying part? No one in the world has a reliable defense against them. That’s the real danger. Even with limited resources, I believe North Korea will pour everything into this."

But Chun's concern isn't just technological—it’s strategic. "The way they operate—through smuggling, improvisation, and speed—they’ll gain the upper hand. Meanwhile, in the free world—Korea, the United States—we’re stuck in a procurement cycle that takes five to ten years. They’ll get it done in five to ten months. How do you win like that?"

His warning is clear. "We have to rethink everything. We’re trying to play by the rules, to be proper, to avoid risk—but if we keep that mindset, we’ll pay a heavy and dear price. That’s my biggest concern."

The nature of warfare is evolving beyond physical and cyber domains into cognitive warfare. How successful can this "fifth generation warfare" be, and how do we defend against it?

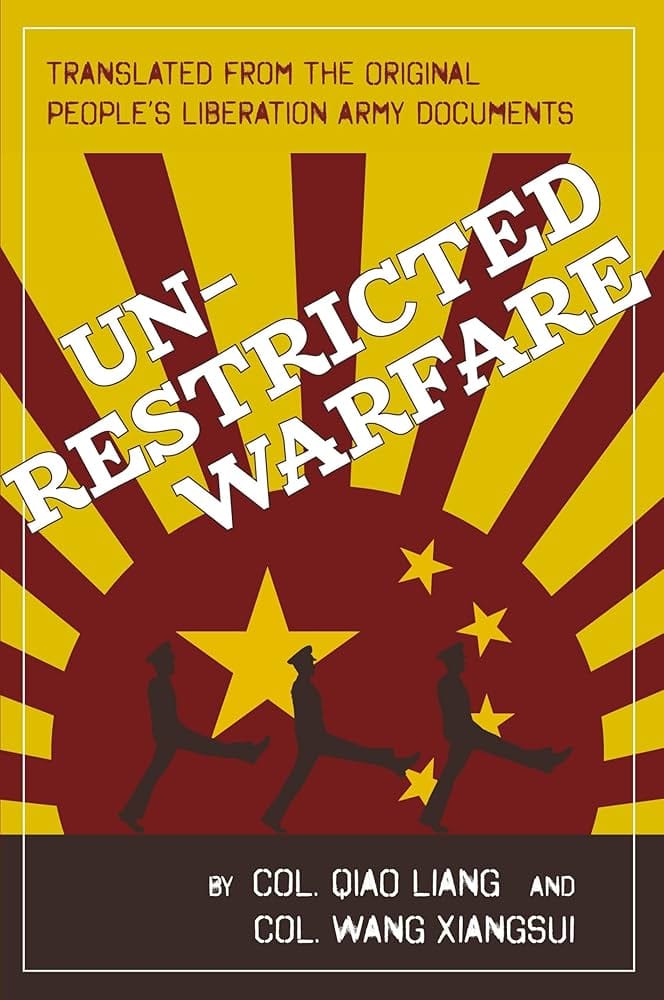

"So in the early ’90s, during the first Gulf War, the Chinese and the North Koreans realized they couldn’t beat the United States militarily," Chun explains. The overwhelming display of American technological superiority in Operation Desert Storm—precision-guided munitions, stealth aircraft, and networked command and control—left military planners around the world stunned.

"They did a full study," he continues, "and they concluded, ‘Okay, we can’t beat them with bombs and missiles, but we can influence how they think. And we can outlast them.’” This was the foundation for what Chinese military theorists later called Unrestricted Warfare, outlined in the 1999 book by PLA colonels Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui. The doctrine calls for defeating a superior enemy by using non-military means—economic, psychological, informational, legal—whatever it takes.''

Chun says this strategy borrows heavily from history. "That’s exactly what the Vietnamese did. And because Americans need to know they’re morally right in what they’re doing, if you cast doubt on that—if you make them question the morality of their mission—then their ability to fight degrades significantly. You can’t beat an American soldier one-on-one. But if you erode his faith in the mission, that’s how you win."

He sees both danger and miscalculation in this approach. "Now, one thing I think our adversaries do underestimate is the patriotism and fighting spirit of the American people. That’s a big mistake. But they’ve figured out that injecting that ‘virus’—that doubt—is something they can do. And they believe they can win through that."

Yet Chun is far more critical of how democratic societies have responded. "Here’s the real issue: we’re not doing enough. Forget trying to influence our adversaries for a moment. Are we even telling our own story—to our own people? And if not, why not?" For Chun, this is not just a missed opportunity—it’s a moral failure. "We have a strong case to make: democracy, freedom, equality. These aren’t just slogans; they’re powerful ideas. But we either take them for granted, or we don’t feel proud enough of the fact that we live in a society that values tolerance, humanity, and the balance between individual rights and collective responsibility."

To him, defending against cognitive warfare is not just about playing defense—it’s about stepping up and telling the truth better than the adversary tells lies. "Yes, we have to defend against hostile influence. But more importantly, we need to communicate with our own people. That’s why I value conversations like this. Maybe, in some small way, I’m helping—not just in identifying the adversary, but in reaffirming why what we stand for matters."

Artificial intelligence raises the stakes even further. "Korea is a wide-open society. And with AI these days—oh my gosh. In the old days, we used to say, ‘Believe half of what you see and a quarter of what you hear.’ Now I’d say, ‘Don’t believe anything.’ So where are we heading in the next decade? Honestly, I’m afraid."

There are already real-world examples. In 2022, a deepfake video of Ukrainian President Zelenskyy urging surrender circulated on social media. South Korea faced its own version of this threat when deepfake pornography targeting thousands of women flooded local platforms.

Chun sees elections as a particularly fragile point. "Here in Korea, we’re deeply concerned about the integrity of our elections. And while there are doubts and suspicions circulating, I still believe that the integrity is intact—because if it isn’t, then everything collapses."

He doesn’t mince words about the threat environment. "Our adversaries know this. They want to influence us. Honestly, I believe half of the problems we face in democratic societies today are the result of deliberate attempts by dictatorships to destabilize us—to convince us that their autocracy is better than our ‘chaos.’ But chaos and freedom are not the same thing."

South Korea’s constant election cycle makes this even more dangerous. "We’re incredibly vulnerable. We have elections every other year—local, legislative, presidential. That’s a recurring event. And every time, we spend not just money on the election itself, but also to protect it from external interference."

He widens the aperture. "It’s not just about cyberattacks or satellite disruptions. The real war is cognitive—convincing people that what they’re doing is wrong, that their system is broken. And today, most people don’t take the time to fact-check. That’s a dangerous place to be."

Even the most closed regimes understand the power of influence. "Take North Korea. It’s one of the most closed-off countries in the world. They’re not afraid of our ICBMs—but they are afraid of K-pop and K-dramas. That’s why they’ve clamped down so hard on outside culture." He’s not exaggerating. In 2020, North Korea passed the "Reactionary Ideology and Culture Rejection Act," which imposes severe penalties—including death—for distributing South Korean entertainment. Teenagers have reportedly been sentenced to hard labor simply for watching K-dramas. "And that," Chun concludes, "is proof that influence works both ways."

Cognitive Warfare: The Battle for Minds

Evolution of Warfare Domains

The Vulnerability Matrix

| Target | Method | Defense Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Elections | Disinformation, deepfakes | "Korea has elections every other year—a recurring vulnerability" |

| Social Cohesion | Polarization campaigns | "Half of democratic problems are deliberate destabilization" |

| Military Morale | Mission doubt injection | "Americans need to know they're morally right" |

| Truth Perception | AI-generated content | "Don't believe anything" |

The Power of Cultural Influence

North Korea's Fear

"They're not afraid of our ICBMs—but they ARE afraid of K-pop and K-dramas."

- Reactionary Ideology & Culture Rejection Act (2020)

- Death penalty for distributing SK entertainment

- Hard labor for teenagers watching K-dramas

Democracy's Strength

"We have a strong case: democracy, freedom, equality. These aren't just slogans."

- Truth as strategic weapon

- Values worth defending

- Storytelling superiority

In closing, you mentioned the North Korean soldiers in Ukraine. Can you elaborate on what that tells us about the nature of the threat we face?

"You know, these North Koreans in Ukraine—Russia," Chun begins, his voice shifting to a more somber tone. "The Ukrainians really try hard to capture them. And yet, when they’re cornered, they blow themselves up."

Videos emerging from the Ukrainian front have shown North Korean soldiers using grenades to commit suicide rather than be taken alive. Ukrainian special forces have reported multiple such incidents—a grim echo of the kamikaze tactics used by Japanese soldiers in World War II.

"When they blow themselves up," Chun continues, "they don’t cry out for their parents. They don’t call for their sweetheart. They say, ‘Long live the Great Leader.’ I mean, brainwashed—highly indoctrinated."

This level of ideological commitment reflects a lifetime of state conditioning. Under North Korea’s Songbun system, citizens are ranked by their family’s perceived loyalty to the regime. Military service, particularly foreign deployments, is typically reserved for those from the most trusted bloodlines—individuals groomed through years of intense ideological training.

"I’ve faced these men all my life," Chun says, the weight of decades etched into his voice. "The interesting thing is, if you manage to capture one alive, give him a hot meal, treat him kindly—these zombies, they turn into human beings overnight."

This transformation is not without precedent. During the Korean War, thousands of Chinese and North Korean POWs captured by UN forces declined repatriation. Of the 21,000 Chinese prisoners held, over 14,000 chose to go to Taiwan instead of returning to Communist China. Thousands of North Koreans made the same choice, preferring freedom to a return to authoritarian rule.

"That is how brittle these societies really are—because they’re built on lies. And that’s why the North Korean regime is so terrified of the truth." Recent actions by Pyongyang underscore this fragility. In 2023, the regime demolished the Arch of Reunification, a long-standing symbol of future unity with the South. Kim Jong-un not only declared South Korea a "permanent enemy," but amended the constitution to officially abandon reunification as a national goal. Many analysts interpret these moves as defensive measures against the growing influence of South Korean culture and ideology.

Chun’s conclusion carries both a warning and a call to conscience. "We are not on the losing side. But we do have our own challenges. That’s the price of our freedom—but there has to be some kind of balance." He leaves us with a quiet but powerful reminder of the moral high ground. "To right a wrong, you must not do something wrong. You must always hold on to who you are—your identity. That’s the challenge we all face. And that’s the one we must overcome."

Author's Analysis

Lieutenant General In‑Bum Chun speaks with the credibility of someone who has stared down North Korea for nearly four decades while translating Korean realities for an often‑distracted American audience. His life story—from a seven‑year‑old Korean boy in 1960s California to a three‑star general commanding special forces—mirrors the arc of the U.S.–ROK alliance itself: improbable, hard‑won, and strategically indispensable. That dual vantage point allows him to critique both Seoul’s complacency and Washington’s blind spots with equal candor.

What makes Chun’s assessment so urgent is his focus on the threats most analysts relegate to footnotes. While nuclear headlines dominate, he shows that Pyongyang has quietly become a top‑tier cyber power by conscripting its best mathematicians and operating entirely outside international norms. His warning that North Korea now ranks with the U.S., Russia, China, and Israel in offensive cyber capability should jolt any policymaker still comforted by nuclear deterrence; malware can black out a grid or hijack an election long before missiles ever fly.

Chun’s prescient reading of the Russia–North Korea axis is equally sobering. He rejected the consensus that ammunition sales would be transactional and short‑lived, arguing desperation would forge deeper ties. He was right: North Korean boots are now on the Ukrainian front, and tech transfers—satellite‑navigation spoofers, drone swarms, anti‑satellite tools—may soon follow. If that happens, Pyongyang will graduate from regional menace to global chaos multiplier, exporting cheap disruption to any autocrat with cash.

His insights on cognitive warfare cut deeper still. A soldier who has watched “zombies” revive into ordinary humans after a warm meal understands both the power and fragility of totalitarian indoctrination. That is why Kim Jong‑un fears K‑pop more than THAAD: a single forbidden music video can puncture decades of propaganda. Chun’s point is clear—truth is not merely a virtue; it is a strategic weapon democracies cannot afford to holster.

Finally, Chun’s prescriptions reveal a pragmatist who knows technology is only half the battle. Commercial LEO constellations, directed‑energy defenses, and integrated radars will matter little without operators who understand them and societies that believe in the values they protect. His call for the West to tell its own story—boldly, honestly, and constantly—reminds us that in fifth‑generation warfare, the decisive terrain is the human mind. Fail there, and even the best lasers will not save us.

About Lieutenant General (Ret.) In-Bum Chun

Lieutenant General In-Bum Chun (ROK, Ret) served 38 years in the South Korean Army and retired in 2016.

He commanded combat units from platoon to the division level and his final command position was Commanding General of the ROK Special Forces. He served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

He is currently a Senior Fellow with the Association of the United States Army. A Distinguished Military Fellow with the Institute for Security Policy Development/Sweden and advises many organizations to include the Korean Counter Terrorist center, the city of Pyeongtaek and Sungnam and is an active YouTuber in Korea. He also advocates for animal rights.

For more information, reach out to Lieutenant General In-Bum Chun at truechun9@gmail.com.

Further reading:

Get exclusive insights from our network of NASA veterans, DARPA program managers, and space industry pioneers. Weekly. No jargon.